Five charts that show us where we are now

The first half of the year has been a tough market environment for investors. Much of the tricky start can be attributed to soaring inflation and central banks belatedly tightening monetary policy across much of the developed world. In the emerging world, many central banks sensibly started raising interest rates in 2021. This has led equity markets to sell off and bond yields to rise. There are reasons for optimism, however, which we will come to.

What central banks are doing

The European Central Banks (ECB) Forum on Central Banking 2022 took place in Sintra, Portugal from 27th - 29th June. The main takeaway was central bank policy makers affirming their number one aim is to combat inflation. The rationale is that overcoming inflation now will avert a much worse situation in the future if continuing higher prices were to become more entrenched.

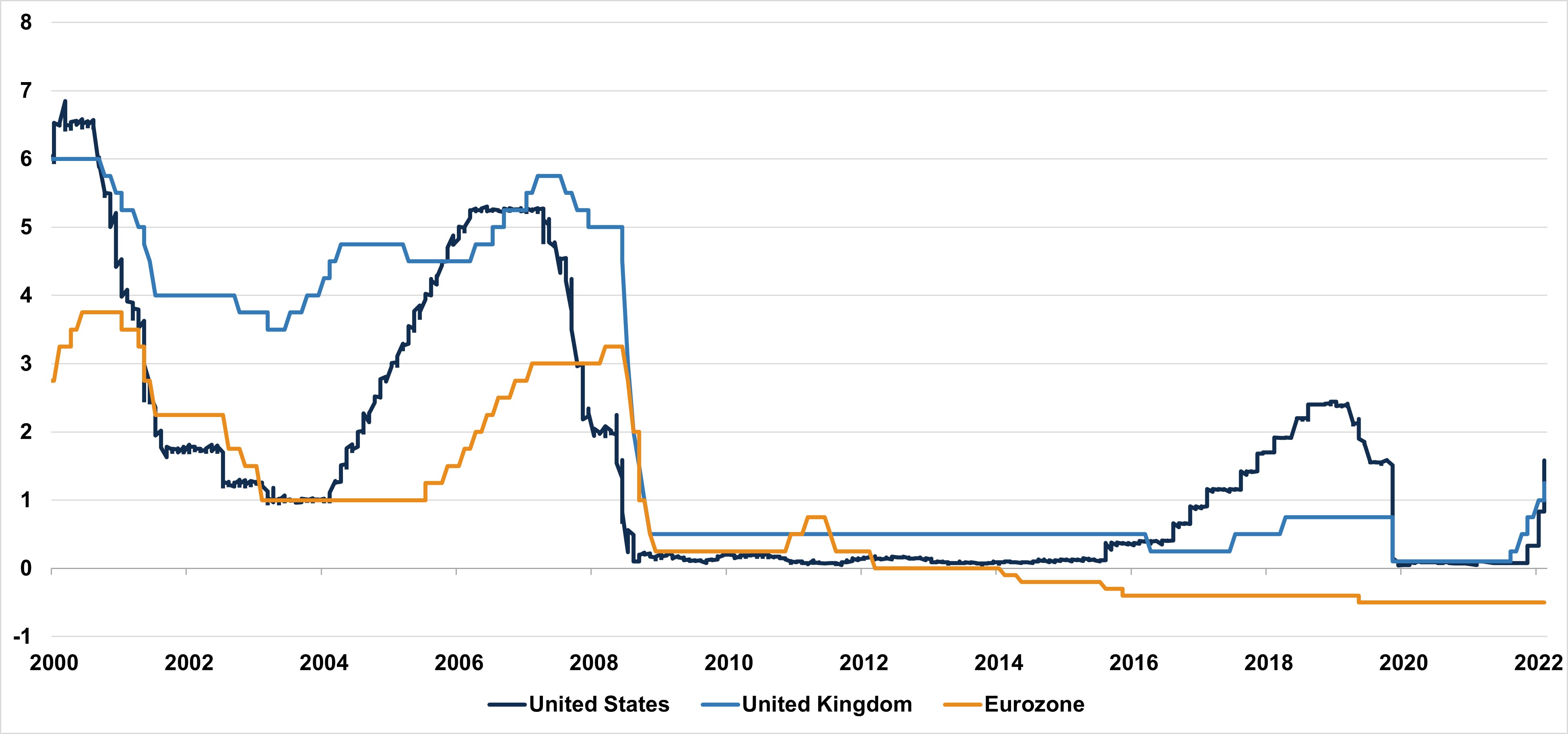

Interest rates (%)

Source: Bloomberg

Central banks across the world have responded differently to the challenges initially posed by Covid. In the East, the Bank of Japan has not moved its interest rate and China is even lowering interest rates presently, as it remains focussed on its zero-Covid policy. At the other end of the scale, Brazil has tried to get on the front foot and raised interest rates from 2% at the beginning of 2021 to 13.25% now.

The Bank of England was initially slow to respond. It has now raised interest rates for five consecutive meetings, leaving the base rate of interest at 1.25%. Further rises are firmly on the table.

The US Federal Reserve (the Fed) was slower in starting to raise rates, but is now going for larger rate hikes, with the last being a 75-basis points hike taking the federal funds rate to 1.5%. Again, further rises are a certainty.

The ECB, meanwhile, has only just ended its latest quantitative easing programme despite inflation in the eurozone reaching 8.1% in May. The ECB is in a particularly tricky situation. Not only does it have high, but varying inflation levels to contend with between eurozone nations, there is also the issue of yield spreads widening between core and peripheral nations.

This means it costs governments more to borrow money in countries such as Italy, Spain and Greece compared to Germany, France, and the Netherlands. Juggling the inflation issues with the differing costs of government borrowing is concerning for the eurozone outlook.

The causes of inflation

First, allow us to answer a simple question: what is inflation? Inflation is the rate at which prices are changing. Its magnitude is largely due to imbalances between supply and demand. If supply is constrained and/or demand is high, prices rise until balance is restored. If supply is plentiful and demand is low, prices fall.

Inflation has hit multi-decade highs across much of the developed world. Initially, the broad market consensus was that inflation would be transitory – it was only rising as a result of extremely low year-on-year base effects. These were a result of low demand and energy prices crashing in 2020 following the first Covid lockdowns. The hypothesis was this would simply pass-through when these low base effects were no longer impacting inflation figures. The consensus was emphatically incorrect.

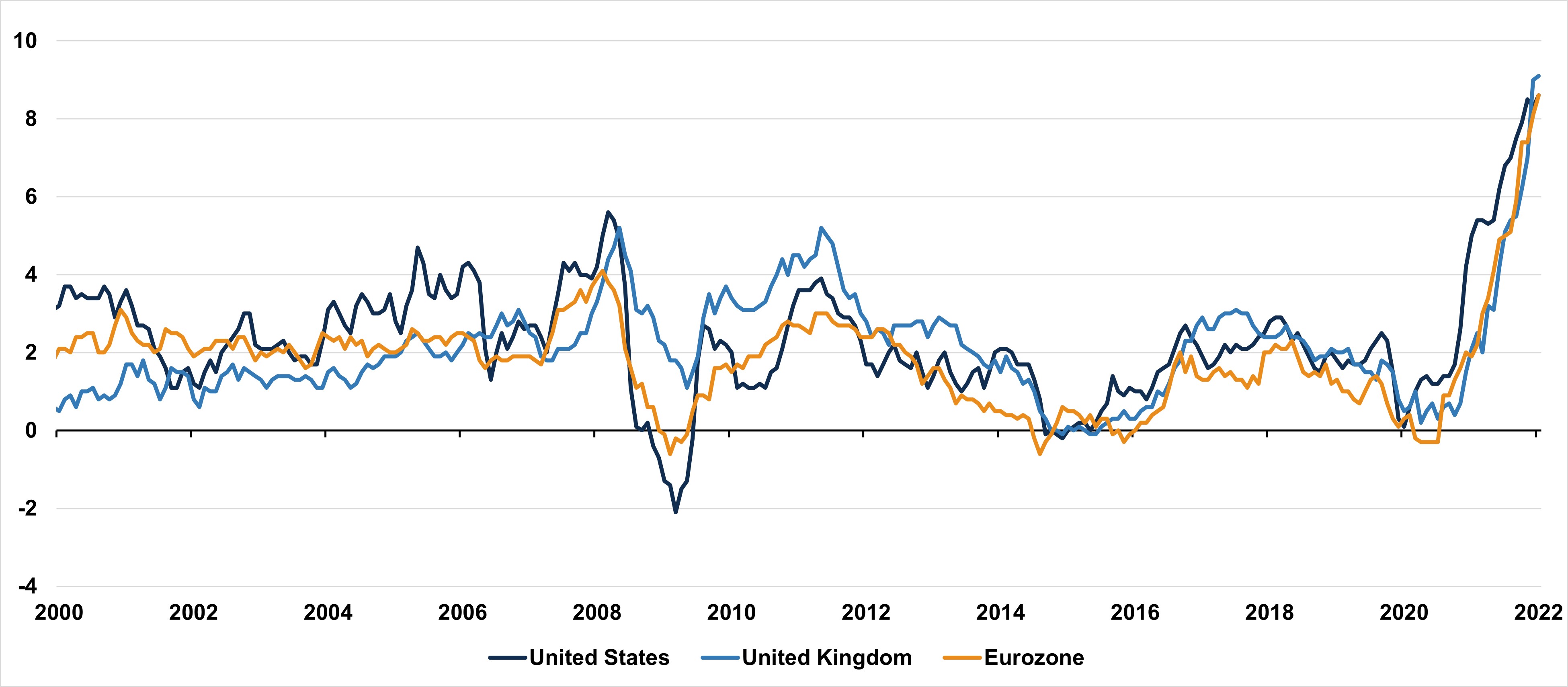

Headline inflation rate (%, year-on-year)

Source: Bloomberg

Central banks, through interest rates, and governments through fiscal policy, can impact the demand that contributes to inflation. The supply-side factors are trickier to control.

Both demand and supply factors have contributed to inflation being elevated today. Consumers spent their accrued savings as a result of lockdowns (creating a rise in demand) and supply chains remain disrupted due to Covid-induced lockdowns, the impacts from the war in Ukraine and energy prices remaining elevated despite the recent sell-off.

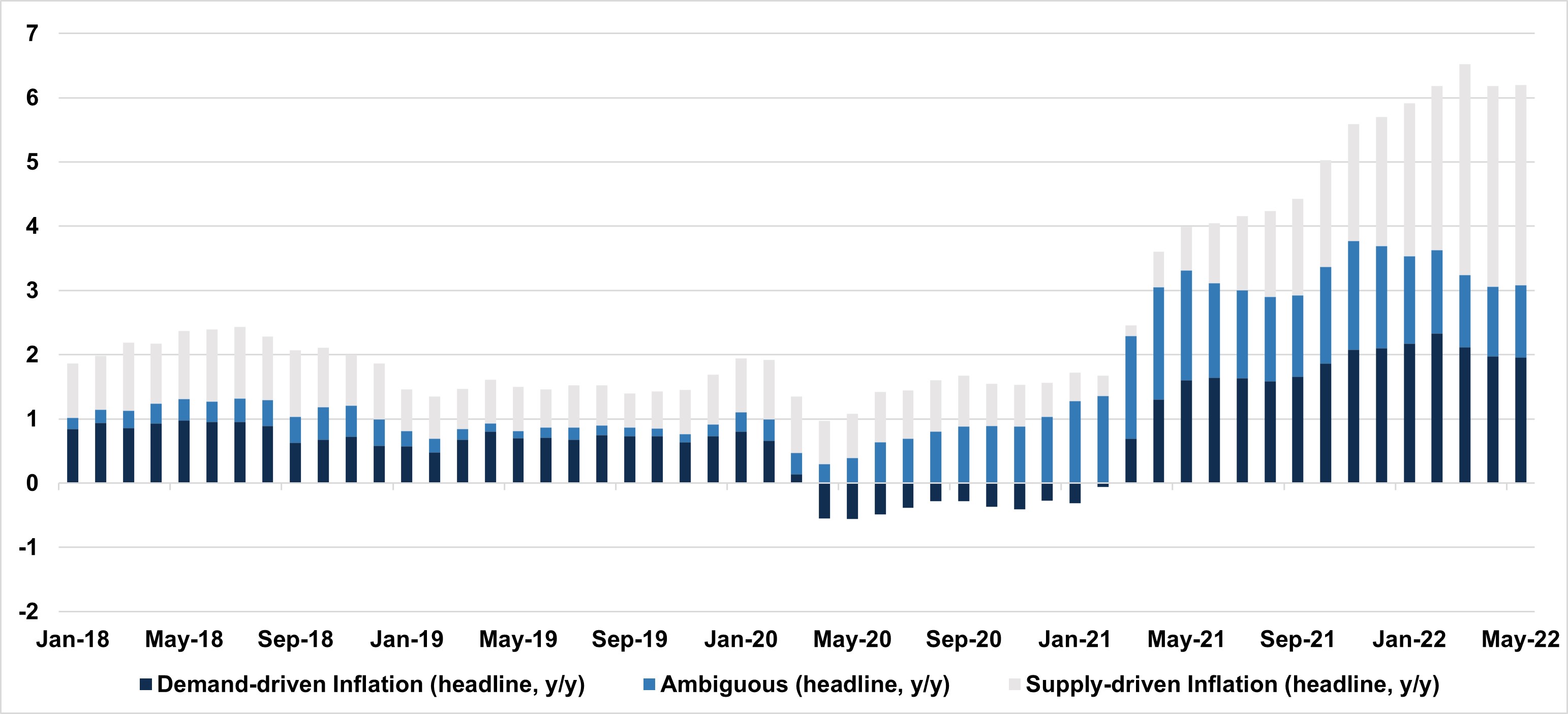

As you can see from the graph below, in May roughly 2% of the 6.3% headline PCE (personal consumption expenditures) in the US is as a result of demand-driven factors. Around 3.1% is supply driven while about 1.1% is ambiguous. Given that only 2%, or less than one third, of headline PCE inflation can be targeted by central banks, they will have to decimate demand to bring inflation down to anywhere near the 2% mark.

Supply and demand driven contributions to annualised monthly headline PCE inflation

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

This is, of course, unless supply-side pressures ease (which they have slightly since the turn of the year – see graph below) significantly. The Fed is not only talking the talk with regard to inflation being public enemy number one, but it is also walking the walk with 75-basis point rate rises. The combination of these points adds weight to the possibility of a US recession through 2023.

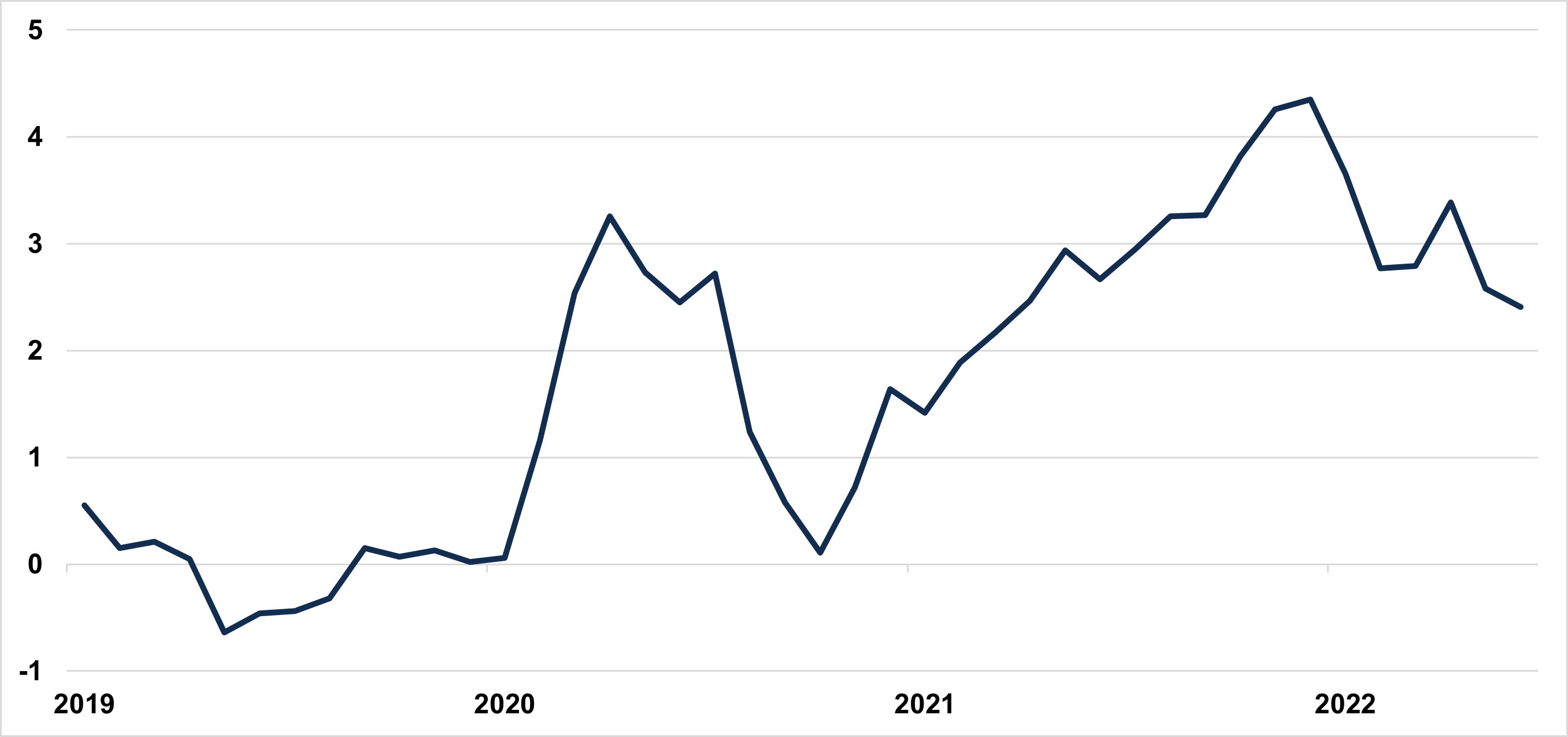

Federal Reserve Bank of NY Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

Source: Bloomberg

It is worth noting the PCE is the Fed’s favoured measure of inflation as it measures what people actually spend their money on.

There are lessons to be learned from the past – particularly the 1970s where the inflation shock was driven in part by oil price rises. The countries that tightened monetary policy earlier were more successful at keeping inflation in check, namely Germany, Switzerland, and Japan. This is partly due to curbing second round inflationary effects such as rising wages. Being on the front foot in the fight against inflation is crucial.

Inflation expectations

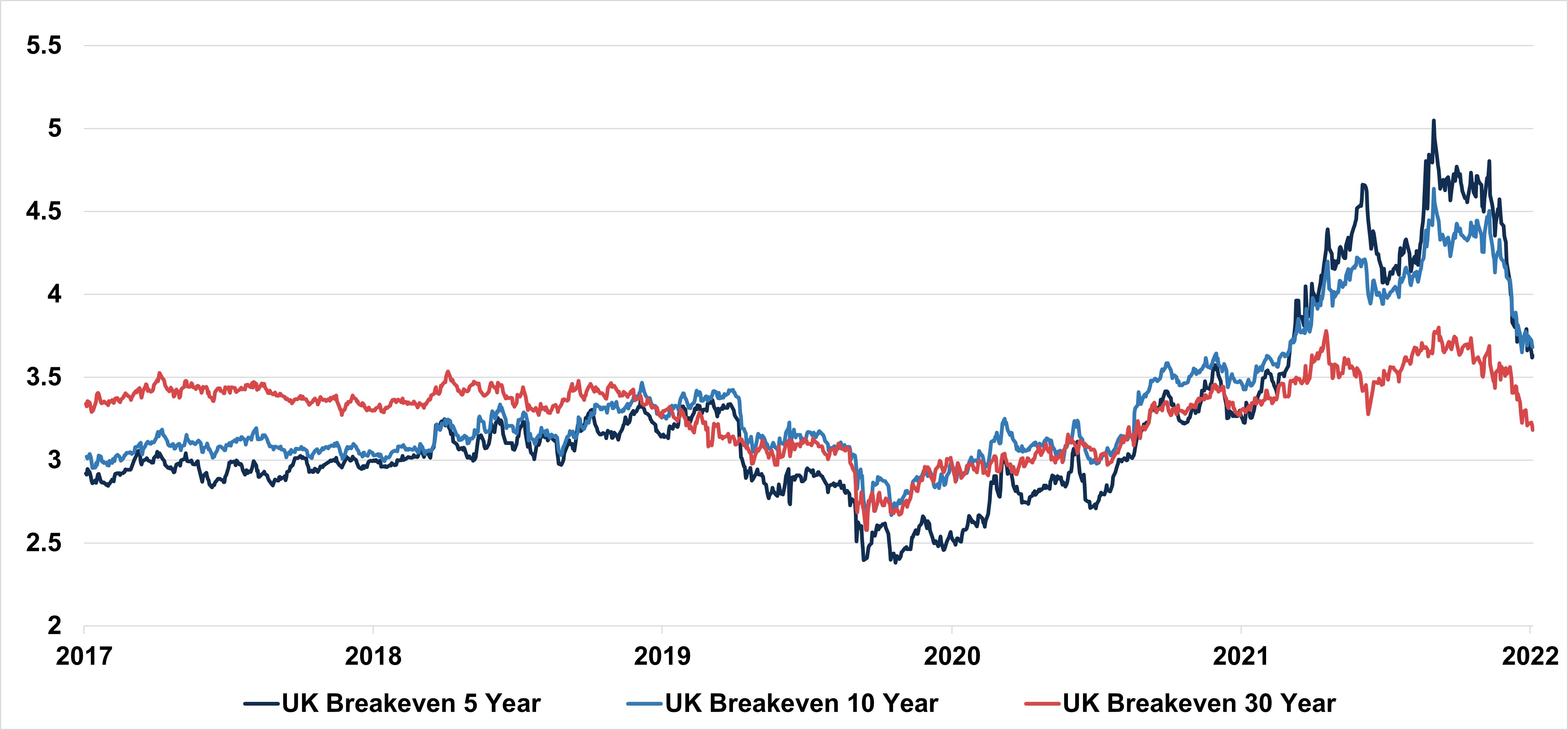

However, there may be cause for some optimism. Markets are saying inflationary pressures will no longer be such a concern in the future. This can be seen in the graph below showing UK breakeven inflation rates¹ (implied future inflation rates) coming down significantly since the middle of June. The same is true of breakeven data in the US.

UK breakeven inflation rate

Source: Bloomberg

The Fed are predicted to raise interest rates until February next year. From February, markets are then pricing for interest rates to be cut throughout the remainder of 2023. Together, these points lead us to the conclusion that markets are pricing that central banks will successfully overcome inflation by raising interest rates and reducing demand and will then come to the aid of economies by reducing interest rates again.

However, the risk of inflation remaining elevated for longer than the market anticipates, or only falling to above average levels, remains.

Whatever happens, we are prepared to adapt

At Netwealth, our seasoned investors and senior team have experienced many economic cycles and challenging environments, and are skilled at adapting to a wide range of scenarios to help us get the right outcome for clients.

If you would like to know more about how we can help you, please get in touch.

Please note, the value of your investments can go down as well as up.

¹ Breakeven inflation rates are derived from the current relative yields on offer from regular government bonds and those whose coupons and principal are lifted in line with realised inflation. In this way, the breakeven rate represents the bond market’s estimate of future inflation, albeit subject to some market technicalities, such as liquidity.