Global Economic Slowdown is Inevitable

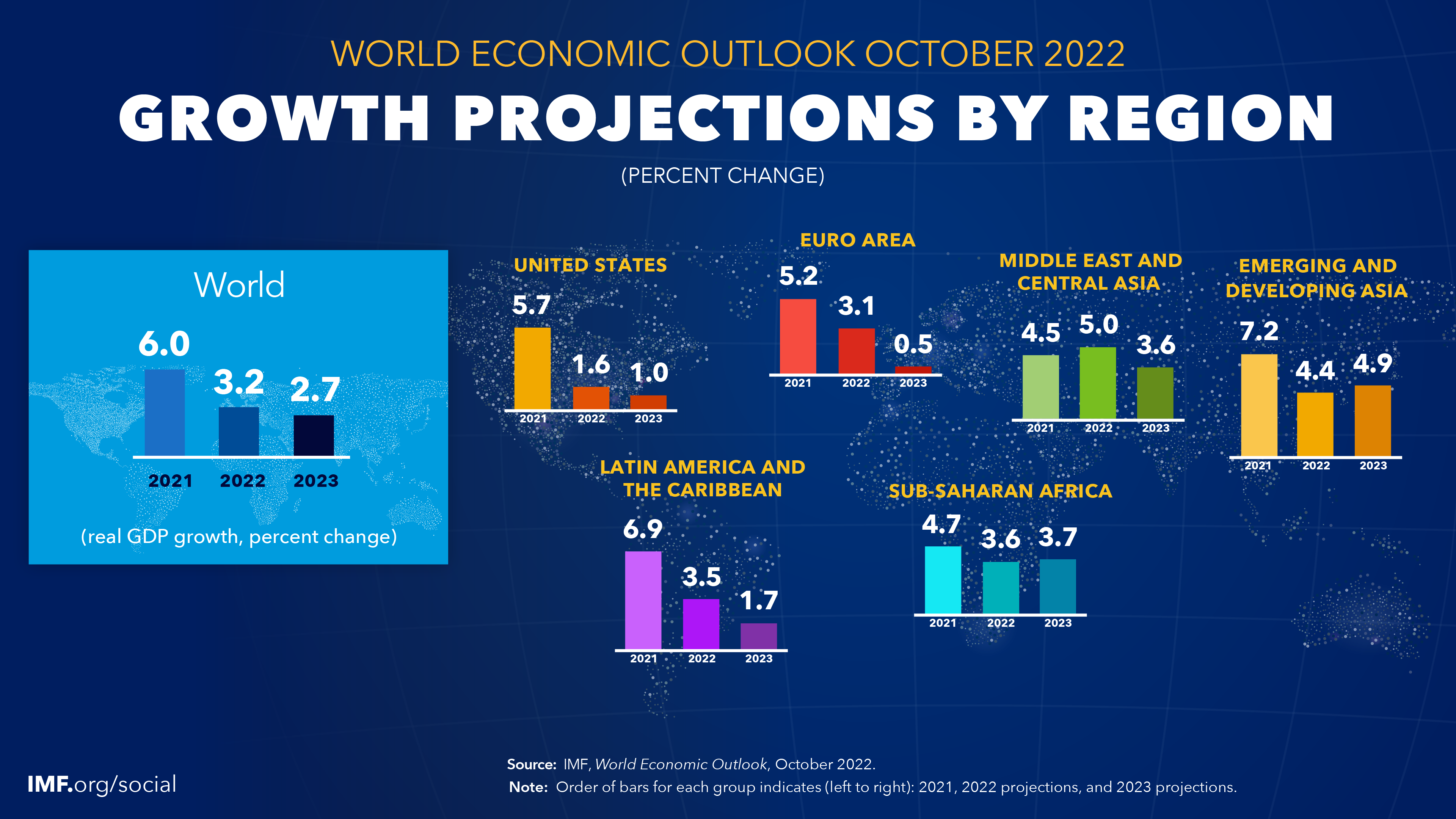

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has just released their global economic outlook. It makes sober reading. But it may yet prove too optimistic about the year ahead. As the chart shows, the IMF sees the world economy slowing from its strong post-pandemic rate of 6% last year, to 3.2% this year and 2.7% next year. On this measure, anything around 3% or below is very weak.

So, effectively the world economy will feel like it is in a recession next year. Europe and the US will be particularly weak. Meanwhile, Asia will be the strongest region, and should witness an upturn from this year. Separately, the Asian Development Bank reports that this year and next will be the first time in over three decades that developing Asia will grow faster than China.

Meanwhile, global trade has picked up slightly. The CPB World Trade Monitor showed trade up 0.7% in July, after quarter-on-quarter rises of 0.7% in Q2, 0.6% in Q1 and a large 3.0% in Q4 last year. These growth rates, while modest, are not too bad. But with industrial production and other measures slowing (such as PMIs in the west), one might expect global trade to lose momentum in the second half of the year and into next.

In fact, it is the weakness of the world’s two major economies that is the major story, alongside the persistence of global inflation pressures.

Inflation persists

Globally, there have been common aspects to the inflation story, notably disruptions in supply chains, and higher raw material costs. And, as the impact of high energy costs has worked its way through, despite oil prices being below previous highs, many countries are seeing high food prices.

On top of that, either the impact of currency weakness versus a resurgent dollar, or idiosyncratic features that have fed second-round effects through higher wages or costs being passed on, has led to inflation persisting and higher global interest rates. In January, inflation this year across advanced economies was expected to be 3.9% according to the IMF. Now, they expect 5.7%. Likewise, for emerging economies, this year’s inflation forecast has risen from 5.9% to 8.7%.

Inflation is the big concern in the US. It is also couching how markets see developments elsewhere too, namely through an inflation lens. The Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (or PCE deflator) has decelerated from its June high of 7%, to 6.4% in July and 6.2% in August. Excluding food and energy, the core PCE deflator, meanwhile, is off its June high of 5.0% but rose from 4.7% in July to 4.9% in August.

Thus, inflation remains elevated. The pick-up in the core rate, too, will feed the Fed’s bias towards tightening. As, too, will the healthy jobs market. The unemployment rate is low, and recently monthly jobs gains have been solid, although consistent with an economy losing momentum.

Even though central banks are, in theory, looking 18 months to two years ahead, because of the lags with which monetary policy works, one could be forgiven for thinking they are very responsive to current data. Indeed, this led policy to be too loose in the US last year (and in the UK), and very much leads to the latest data releases driving the present policy debate.

While it is the regular policy meetings of the Fed’s FOMC that are the focus of market attention in the US, in contrast, all eyes on China throughout this year have been focused on the 20th National People's Congress, which is just concluding in Beijing.

China politics

Xi Jinping’s imminent appointment to a third term was always expected. The issue, though, has been what this means for the economy and policy. Attention for many was on the comments regarding Taiwan and “national reunification by peaceful means”. This was hardly surprising and is a confirmation that geopolitical issues will persist, but are hard to predict or plan for.

On the economy, the main takeaway was a reiteration of the focus on “high quality development” from five years ago. In essence, China trying to move up the value-curve. Also, hardly surprisingly, there is a continuation of current policy, with China seeking self-sufficiency in areas such as technology.

Over the last couple of years, the economy has faltered for a combination of reasons, including the pandemic and the official zero Covid policy, and because of policy shifts that seemed to be hitting the private sector in areas such as tech and tuition. Also, because of the overhang of debt and persisting problems impacting the property sector.

It was hard to determine any immediate change in addressing immediate economic challenges (such as sluggish growth and high youth unemployment) from the work report that was released at the start of the Congress. Previously, whenever the economy has faltered it has triggered monetary and fiscal easing.

Now, though, the room for fiscal manoeuvre is limited. Monetary policy, meanwhile, has already been eased this year, and while this has been gradual, it is in sharp contrast to the west. In turn, the CNY (Chinese Yuan) is weak.

In the past, the combination of a stronger dollar, higher US rates, and a weaker CNY have not been a good backdrop for emerging economies.

Managing euro risks

Finally, developments in the euro area, as in the UK, have been heavily impacted both by the war in Ukraine exacerbating the inflation data, by necessary fiscal action and higher rates. As elsewhere, there are major policy trade-offs between inflation versus recovery, and between limiting public debt levels from rising further versus timely and targeted fiscal help.

The nature of the inflation shock in the euro area is different from that in the US, which is driven more by a strong and overheating domestic economy. In the euro area it is the energy shock, plus lax monetary policy. (The UK has aspects of both, perhaps.)

In the euro area, again as in the UK, domestic demand is losing momentum, while energy price challenges have persisted. A flash estimate suggested headline inflation would reach 10% in September. It reached 9.1% in August, with core inflation at 4.3%.

Already the European Central Bank is tightening, with the main policy rate having risen from -0.5% but it is still low, at 0.75%. The market expects this to rise to 2% by the end of this year and to peak at 3% next July. If inflation pressures ease, as is generally expected, then the market forecast may appear to be broadly where it should be.

The sovereign debt crisis that followed the last period of euro area interest rate tightening has left its mark. While markets do not believe this is the most likely outcome, they fear a repeat, given that sovereign debt levels are high, and that sovereign spreads could widen further as monetary policy tightening unfolds. However, policy makers appear determined to avoid such a repeat, both through support and by moving gradually on rates if needed.

Overall, it remains a difficult global backdrop as the world economy adjusts to monetary tightening and to a continuation of geopolitical tensions.

This is the second of two simultaneously released Our Views. The accompanying one is on the UK economy.

Please note, the value of your investments can go down as well as up.