How Global Events Impact Your Investments

In our latest investment update, our Chief Economic Strategist, Gerard Lyons, and our Head of Portfolio Management, Iain Barnes, look at the events that are impacting the global economy and financial markets, and what this means for your investments.

Gerard Lyons

The UK and the global economy are returning to normal after the pandemic, but the economic rebound is triggering a whole host of issues. We've seen a rise in inflation. We're seeing concerns about exit strategies by central banks, and, indeed, by governments from their high levels of debt, and worries have also now arisen about the sustainability of the rebound that we're currently experiencing.

Over the last half year there has been an evolution in terms of these key issues. Six months ago, markets were focusing on the rebound as vaccines were rolled out, economies rebounded from the depths they hit last year, helped by reflationary policies. Then the situation evolved into a worry about inflation. More recently, the focus in markets has been about a deceleration in economic growth.

Naturally, the rates of growth economies are seeing at the moment cannot be sustained. But six months ago, the feeling was also that growth rates would start to return to some sort of normality after the initial post-pandemic rebound. Now there are worries about a slowdown – partly because rising costs and inflation are starting to squeeze incomes both here and globally – and because of concerns about those exit strategies that I referred to above.

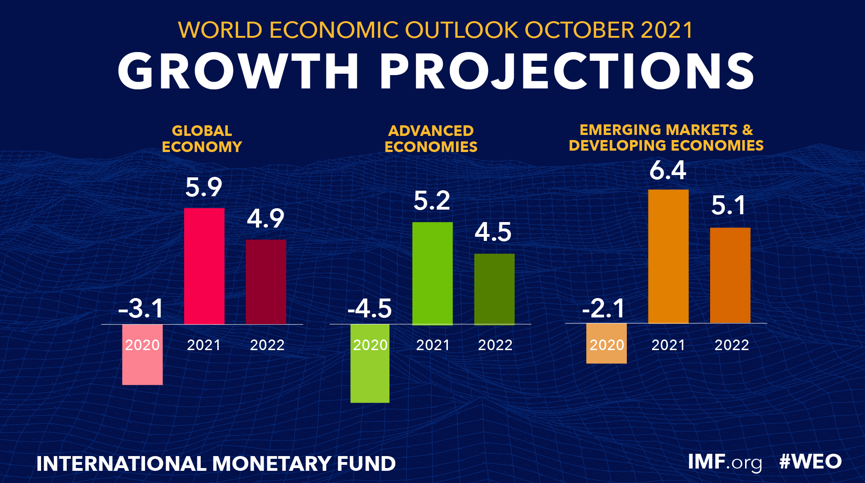

Let's highlight this in terms of the growth picture. Earlier this week, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) started their annual meeting in Washington. While the IMF is not necessarily the best forecaster of the world economy, they are seen as a good barometer of where opinion is. Here is their latest projection:

Let's look at the left-hand side, the global economy. Last year, the global economy suffered a deep recession because of the pandemic. This year the global economy is witnessing a strong rebound, maybe more than some people thought was possible a year ago, but actually slightly weaker than forecasters thought might be feasible about only six months ago. It shows how sentiment changes, but nonetheless, it's a strong recovery of 5.9%.

While growth is projected to lose some momentum, it’s still pretty strong next year at 4.9%. In 2023, the general expectation among forecasters is that growth rates will slow further but back to somewhere around pre-crisis trends.

Also, as one can see above, the IMF sees the recovery being strong in advanced economies – Western economies – but even stronger still on the right-hand side, across the emerging economies.

Interestingly, the IMF believes the UK economy will grow 6.8% this year. That's slightly weaker than its forecasts a few months ago of 7.1% growth, but even its 6.8% forecast would leave the UK as the fastest growing G7 economy this year. The economy is set to reach its pre-pandemic level, as we thought it would, before the end of 2021.

Whether it's the UK economy or the global economy, we are witnessing a combination of rebound from the pandemic – helped by the vaccine rollout in Western economies – and we're starting to see the continued impact of reflationary policies. As we have seen recently in the financial markets, there are still concerns about the future pace of growth in China and one or two other countries, so one should not assume that it's a smooth path ahead. But the key message is that there is an economic recovery underway.

Assessing the inflation outlook

The second area to focus on is inflation.

At Netwealth we have been asking the question for some months about which inflationary pressure it is. Is this pick-up in inflation going to pass through quickly? Is it going to persist, or will it become permanent?

Central bankers, in general, throughout this year have said that the rise in inflation we're experiencing is temporary, due to one-off factors. They're saying it's not permanent.

I would agree with them. However, as we've highlighted before, and as we're actually now witnessing, we felt that there was a danger that the inflationary pressures being experienced could persist. Not just here in the UK, but in other Western economies as well and indeed that is the case.

What we're seeing is a combination of factors coming together. The pandemic has led to major distortions in supply chains. And that's the initial focus of where people look to when they try and get to the bottom of what's causing this pickup in inflation – transportation costs have risen.

But it's not just that, we're also seeing costs pick up across most economies in all sorts of areas. Here in the United Kingdom, for instance, we've seen wage pressures rise and unit labour costs increase as firms try to get back to normal. At the same time, in many sectors, there is the ability for companies to raise their profit margins, not only passing on higher costs, but actually building in a bit more margin as people start to spend.

There is a wide combination of factors, and on top of that, monetary policies have been loose, particularly here in the UK.

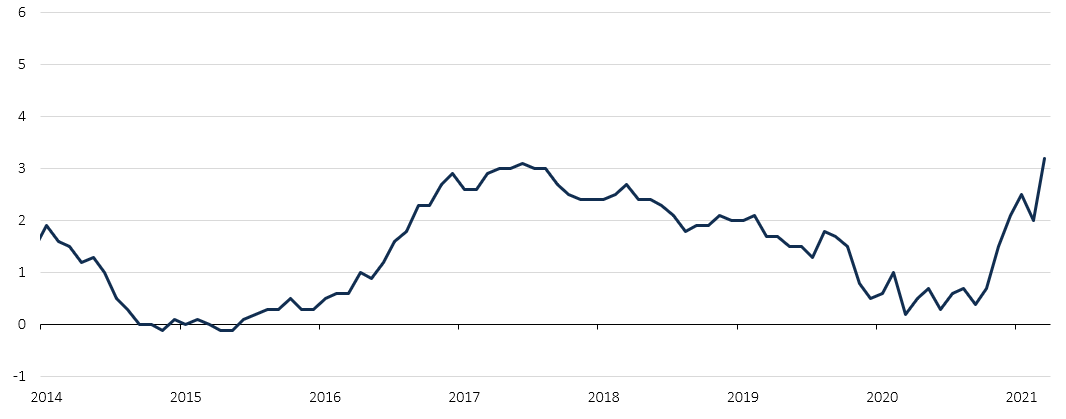

So inflationary pressures are persisting, what does that mean? It means that the UK rate of inflation won’t necessarily return to its target rate of 2% anytime soon, which we can explore further in the chart below.

UK headline inflation rate (%, y/y)

The Consumer Price Index, which is the rate that the Bank of England has the target for, is now 3.2%. Unfortunately, the retail price index (RPI) is 4.8% at the moment, so that tends to compound the squeeze on people's disposable income as the RPI sets the rate at which rail fares and the interest on student loans rise.

While the CPI is now up to 3.2%, it looks set to go above 4.5% before the end of this year and is likely to hit 5%. It would be the consequence of a major policy mistake for it to reach 10% as some people fear. But we are seeing inflationary pressures build and we believe that inflation will remain above the target over the next year and possibly slightly longer.

The policy environment

The third area to look at is policy.

Looking at the policy environment, we currently have a very difficult situation globally. Public debt levels are at an all-time high. Policy rates are low, although rates have risen recently in one or two countries. Central banks’ balance sheets have become bloated and also, financial stability risks have become more of a focus, highlighted recently by the worries in China’s property market and the global focus on the property firm Evergrande.

So we’ve got fiscal concerns, monetary concerns, and additionally financial stability concerns – a whole host of areas to keep not just policymakers occupied, but to keep us all on our toes.

Let's focus on monetary policy, that's the key in the very near term.

Low policy rates (in the UK they are at 0.1%) mean that financial markets do not price properly for risk. In addition, because of quantitative easing (QE), central banks, including the Bank of England, continue to buy assets. The key asset they are buying is government debt. As a result, bond yields are not reflecting true demand and supply because the biggest buyer recently has been a non-commercial player, namely, the central bank.

This has raised questions as to what constitutes a risk-free asset, and it also raises the question: how should central banks tighten policy? Should they tighten by raising interest rates, or should they exit cheap money by tapering, by reversing their QE?

I have written in The Times and other newspapers about my preference. I said a few months ago that the Bank of England should tighten immediately, gradually and predictably so as not to cause shocks. I felt they should exit via reversing QE to take liquidity out of the system and to leave policy rates where they were.

The markets previously thought that the Bank of England would hike rates in February. Now there is a possibility they could hike as early as November – from 0.1% to maybe 0.25%, or potentially to 0.5%.

One of the reasons they're having to do this is because they've been slow to act, but also somewhat because the markets have already done the tightening for them. Ten-year gilt yields have risen significantly in the UK, partly because the market, looking at what was happening not just on the growth front but on the inflation front, felt that the Bank of England needed to act and would have to act.

So to conclude: central banks have intervened significantly across the globe. The question is, how do they exit? Do they exit by tightening, by pushing interest rates up, or do they exit by tapering? In the US, they've hinted they will exit via tapering, therefore delaying their rate hikes for some time. But here in the UK, you should anticipate a policy rate hike relatively soon.

Iain Barnes

We periodically make changes to portfolios to actively reflect views on the market and economic environment, and we have made two changes last week. The first of these relate to the bond market.

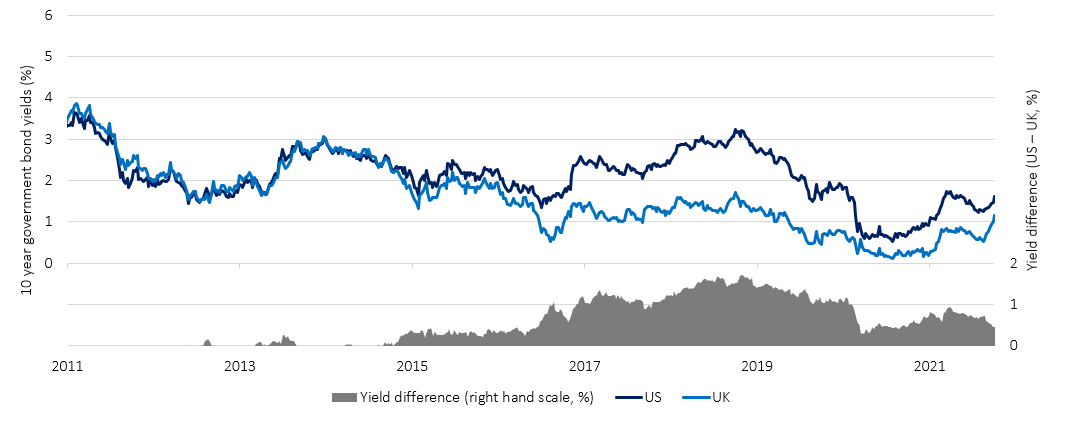

We've had a lower than normal weight, or allocation, to UK government bonds (also known as gilts) since 2019, preferring instead to focus on the US Treasury market – the equivalent government bonds issued by the US. We felt that the level of yield within the US was more attractive and that there would be pressure through time for the UK gilt market to start to yield more as a sign of a normalising environment.

The chart below shows the relative level of yields through time in these two different parts of the bond market. The navy blue line shows the prevailing yield in the US, whereas the light blue line shows the prevailing yield in the UK. The grey shaded area at the bottom is the difference between the two.

US and UK 10-year government bond yields

Switching to US government bonds in 2019 for our client portfolios really had a strong benefit from both the extra yield received by investors, but also from a price performance point of view as that gap narrowed. From the point of inception in 2019, the gap narrowed from about 1.5% in 2019 – when the US were seen as a strong economy and the perception was that the UK was still struggling – to about 0.4% last week.

As that gap has narrowed, it's a sign that the market is thinking that the UK will be either economically strengthening or having to deal with greater inflationary pressures than the US. We see meaningful impediments to UK yields accelerating much further beyond the US. So we've closed that position and added back to gilts. It's important to note that we still do own a lot of US corporate bonds. In fact, relative to the UK, we still see that market as a little bit more attractive.

It's important to note that the changes we made are a reflection of the change in the relative attractiveness of the two markets, rather than a statement about broader inflationary pressures and the direction of yields as a whole, as we switched about 4% of relevant client portfolios from one market to the other.

Moving in and out of commodities

The second change we made to portfolios also relates to the overarching question about growth and inflation that's been dominating macroeconomic conversations over the past 18 months. In March, we made an investment into a broad commodities ETF for our client portfolios.

Commodities tend to do best in specific periods where there is a level of surprise generated about global growth or about inflation. We do not hold them as one of our more strategic asset classes to generate returns through time. In this instance, we held them in preference to high yield bonds, which have done particularly well since the global financial crisis, benefiting from low interest rates and relatively anaemic levels of growth.

Our cyclical position in commodities started in March and had a target performance of 15%. We debated closing the position at our last investment committee meeting as portfolios were close to hitting that price target. The committee decided that the momentum was such that we wanted to retain the allocation and raise that ambition for the level of performance a bit further.

Since the end of August much of the accelerated returns from commodities have been generated by the energy components within the commodity index. Some of the other assets, such as industrial metals, have started to perform more weakly recently. That's often seen as a sign of how investors think this higher energy cost will act as a brake on economic growth.

We took that as a signal that the specific reasons why we've held commodities in portfolios has probably run its course. So last week we decided to remove commodities from client portfolios.

Having seen commodities deliver our specific objectives, they were removed from portfolios last week. The position contributed up to o.5% of total portfolio returns, which was pleasing given the modest allocation. As things stand, inflationary indicators and assets that tend to reflect inflationary expectations have all performed pretty well recently and sentiment appears very one-sided on this theme. At the moment, therefore, we are reassessing how best to continue to embed a little more inflation protection within portfolios.

Where are we in the economic cycle?

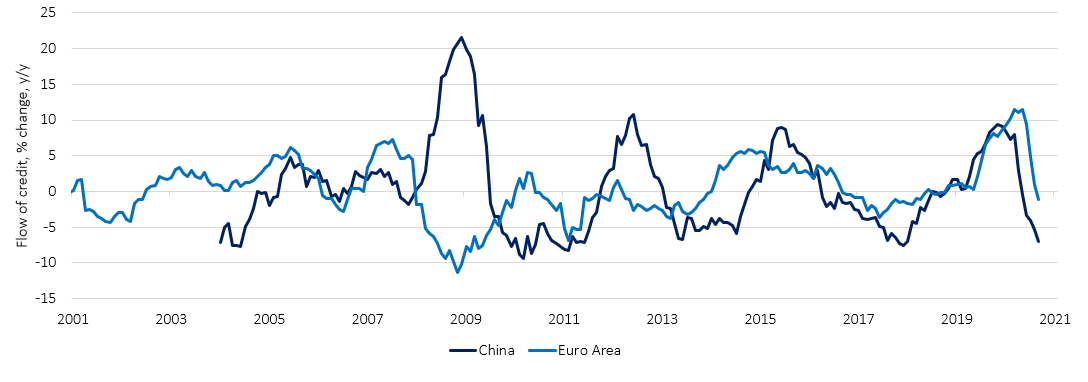

It’s always imperative and interesting to try and assess where we stand in the economic cycle. The chart below, showing the credit impulse in China and Europe, is a good gauge of that.

Credit impulse

The credit impulse is the measurement of the change in the flow of credit that you see year on year. It tends to go hand in hand with signs of economic growth. There's a big unresolved question at the moment about the state of labour markets, and also in terms of end demand. But there are some signs that the level of expected growth globally is starting to slow.

Ordinarily, you might see a dip in the credit impulse as being a sign of deteriorating economic conditions. Whereas at the moment, it's just signifying that we're returning to pre-pandemic lending conditions.

We suspect that is a consequence of increasing energy costs, but also, of course, monetary policy, which is both an input and an output in terms of where we are in the cycle.

At best, I think we can say that we're in the middle of the cycle now, which historically is quite a good area to be in for equity markets. We haven't made any changes to equity markets exposure recently, but it's obviously an area that we focus on in great detail.

US consumers are still spending, but supply risks persist

When we think of one of the key drivers of equity market performance, it is, of course, consumer demand. The strength of the US consumer has historically been a key driver of economic growth. Many companies whose shares that we invest in via ETF exposure are driven by consumer demand around the world, but particularly by the US consumer. And over the past year or so we have witnessed that consumer confidence in the US is still relatively strong.

That's one of the reasons why company profit expectations are also quite high. One of the features throughout all of the macro variations that we're seeing at the moment, is that companies have been delivering good profits, or, as we call it, earnings per share.

The MSCI World Index for example – which covers a wide span of companies worldwide but is quite dominated by US firms – saw a big dip in 2020 but this year has delivered around a 40% uplift in profits generated.

The consensus, too, is still for strong earnings growth in subsequent years with high single digit percentage increases in profits expected for each of the next couple of years. That's clearly a sign of strength and should suggest a robust outlook for equity markets.

Yet we also need to remember that that level of expectation in itself creates some risk. We know equity markets have performed well and the signs are that they expect stocks to keep generating profits, so there is quite a high hurdle now in terms of expectations. It’s important to note that in the current earnings season, these expectations are largely being met.

However, any disappointment on this front, combined with some of the macroeconomic uncertainties, might suggest a little bit more volatility than we've seen recently. It is perhaps timely then that we look at one key risk that keeps cropping up – and that is this question of the supply chain.

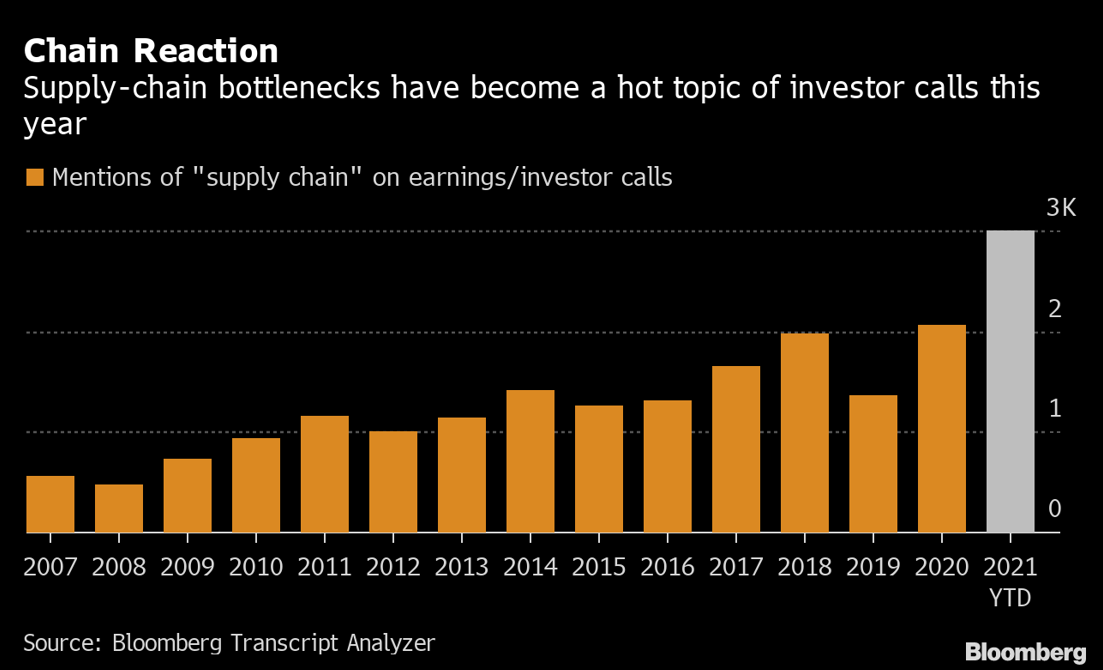

The graphic below is from a Bloomberg analysis of investor calls during earnings season, where companies communicate to analysts their expectations of how well they are going to do in the future. As you can see, mentions of the phrase ‘supply chain’ has been far more significant this year compared to previous periods.

That trend is continuing so far this quarter, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it's a bad thing. Retailers such as Dunelm and companies like Domino’s both reported this week and suggested that their supply chain issues are surmountable, with a favourable market response.

We know that it's not necessarily a challenge for all companies, or it is at least a challenge that some companies are meeting, but it's a key risk that is out there for corporate earnings and something that we need to be aware of through the last quarter of this year.

Please note, the value of your investments can go down as well as up.