Currently, the consensus globally appears to reflect a mixture of all of these, namely recovery, inflation and future slowdown. In turn, markets appear to have been reassured by the US Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) message – which admittedly is a message that the markets wanted to hear – namely that there will not be aggressive, or premature policy tightening.

In my view, there is not enough focus on financial stability risks. These risks are high. Policy rates of close to zero mean markets are not pricing for risk. Also, central banks being the biggest buyers of government debt, in the UK, US, euro area and Japan, should be a concern, meaning yields are not reflecting true demand and supply, with the biggest purchaser in these markets being a non-commercial buyer. While I have highlighted this before, it is worth reiterating.

This does not mean we will see a repeat of the 2008 crisis. But one characteristic of that period is worth bearing in mind now, namely the risk of ‘crowded trades’, where there is much investment in similar assets in the expectation that one can always exit before others.

From an investment perspective this, naturally, favours a diversified investment portfolio.

It is not just financial stability, but monetary stability, too, in terms of inflation that is a concern. The recent acceleration in inflation should not be a surprise.

Inflation is high, but reassuring messaging from the Fed

Over the last week, there has been poor inflation news in the US and China. Take the core rate of US consumer prices, which excludes the more volatile food and energy components. This core rate accelerated sharply during the second quarter (rising 0.9% from the previous month in April, then 0.7% in May and 0.9% in June) and was then subdued during the third quarter (up 0.3% in July, 0.1% in August and 0.2% in September), but rose sharply again in October, up 0.6% on the month, and up 4.6% on the year.

In October the overall rate (including food and energy) rose 0.9% on the month and 6.2% on the year. These are large increases, and reflect that firms are not only facing higher costs but are passing these onto consumers.

In China, producer prices are up 13.5% on the year, and although consumer price inflation is low, it rose from an annual rate of increase of 0.7% in September to an annual rise of 1.5% in October. In China, though, it is the recent slowdown in growth that is the bigger concern.

In the UK, meanwhile, the current rate of inflation is 3.1% and is expected to rise sharply.

In the early 1990s, the market and the consensus adjusted slowly to the move from a relatively high to a low inflation environment. Likewise, a similar development was evident in the first half of the 1970s, only in reverse, as at that time the move was from low to high inflation.

Markets, though, have taken their reassurance not from the data, but from the message from the Fed, which is that it will exit from its asset purchase programme gradually, with hikes in interest rates to follow later. President Biden needs to decide soon whether to reappoint Jerome Powell to a second term as Chair of the Fed or opt for a new Chair with Lael Brainard seen as the most likely alternative.

While a change might have an impact on bank regulation, when it comes to interest rate policy both appear to have similar views. The Fed’s dovish stance was reiterated by Fed vice-chair, Richard Clarida, over the last week that a rate hike was some time away but that the conditions could be in place for a hike by the end of 2022.

It is this stance that US markets, and in turn global markets, are reacting to: US rates are set to stay low for a while and then rise gradually. The markets are also assuming that rates will peak at a low level, with this tightening cycle, when it comes, not being an aggressive one. That, though, will depend upon inflation.

The growth picture

What, then, of growth? As we have seen recently, the recovery is still vulnerable, stalling in response to poor news regarding the virus. Despite this, the overall picture is that this year will see a rebound in the global economy, and while next year’s growth rate will be less than this, it will still be at a higher rate than before the pandemic.

The deceleration in economic growth will continue, so that by 2023 the global growth rate will be back to around pre-pandemic rates. For the bond markets, this is seen as justifying low yields.

The major disruptions triggered by the pandemic should correct as we move through 2022.

Yet the rise in inflation, with higher oil prices and costs, could dampen growth prospects. One economy that faces a cost-of-living challenge in coming quarters is the UK, with higher inflation and rising energy costs and, also, taxes are set to rise next spring.

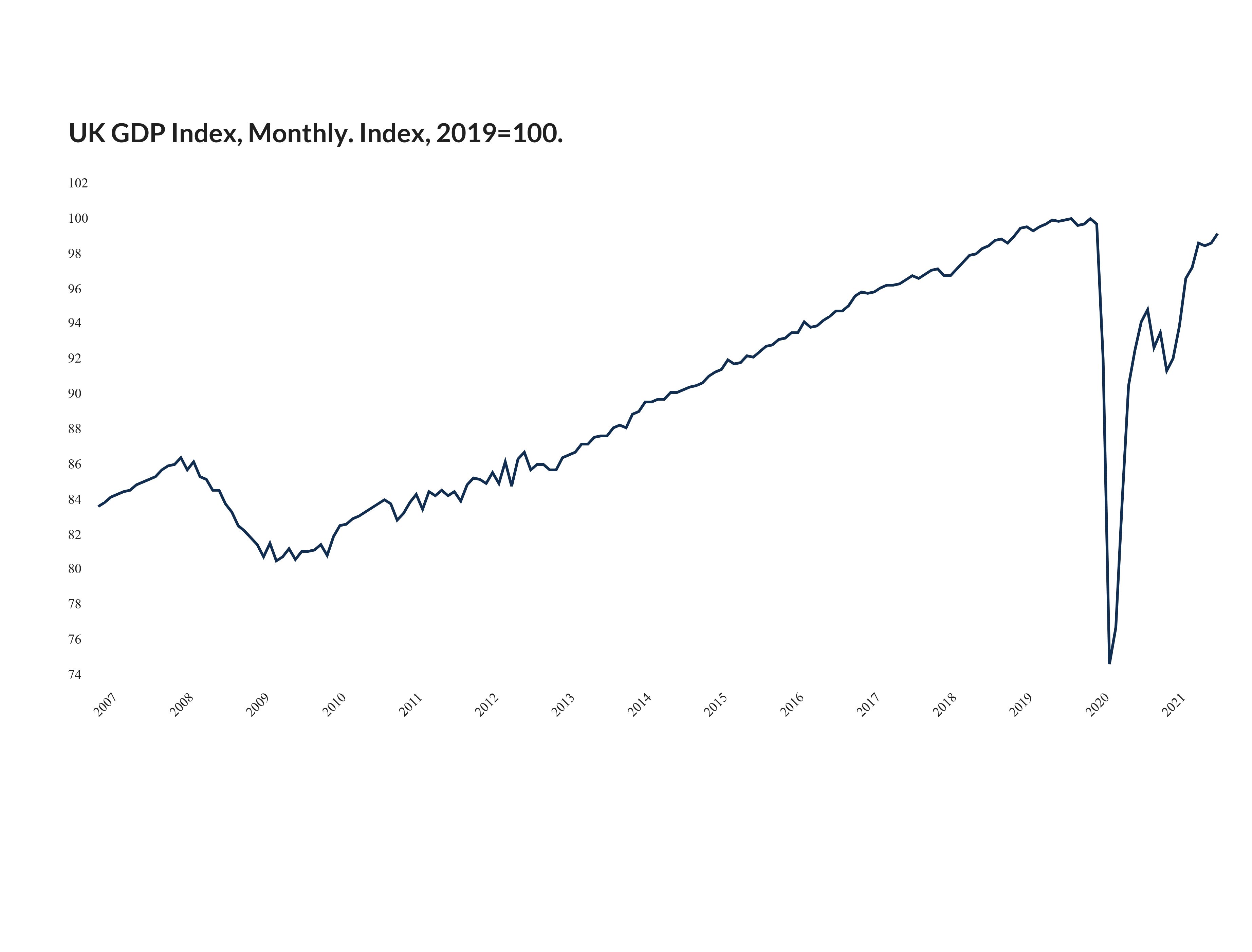

The latest data, though, confirms that the UK economy is recovering steadily. In the third quarter (July to September) the UK grew 1.3% from the previous quarter. This was a slowdown from the 5.3% quarterly growth rate seen during April to June, but this deceleration was not a surprise as the rise in Q2 was particularly strong and health worries had re-emerged at the start of Q3.

On a quarterly basis, the pre-pandemic peak was the fourth quarter of 2019. The economy now is 2.1% below that pre-pandemic level. On a monthly basis, however, the peak before the pandemic was in February 2020, as the economy weakened significantly in March 2020, as people and firms had already adjusted their behaviour before the official lockdown in late March.

The economy then collapsed in April 2020. It then had a solid rebound to October 2020, before weakening again under fresh restrictions, until hitting another low in January 2021.

The latest data shows that the economy gathered momentum during the third quarter, falling 0.2% in July, rising 0.2% in August and then bouncing 0.6% in September. Recent employment data has been solid, too.

UK GDP is estimated to have grown by 0.6% in September 2021, but remains 0.6% below its pre-coronavirus pandemic level (February 2020).

Monthly index, UK, January 2007 to September 2021

Source: Office for National Statistics – GDP monthly estimate

By September the economy was 8.5% above its level of January this year, but still 0.6% below its pre-pandemic level of February 2020. The UK economy should be back to that February 2020 level before the end of the year.

Despite returning to this level, the UK will still be below where it might otherwise had been had it grown in line with its pre-crisis trend. Also, the profile of the economic hit from the pandemic has varied across countries. The UK economy contracted more than its peers last year and is likely to have grown more than other G7 countries this year.

Other major Western European countries will return to pre-crisis levels early next year. The US, though, has already returned to its pre-crisis level, and China, while not part of the G7 did not contract last year.

The prospect of slower growth next year may suggest we will soon be past the peak of the cycle, but as we have seen over the last year the environment can change quickly. Health risks may be fading and instead inflation and policy risks may be coming to the fore.

Please note, the value of your investments can go down as well as up.